How to Choose an Antenna?

In the field of wireless communication, antennas often play a crucial role. As the core components for signal transmission and reception, their performance directly impacts the quality of wireless communication. When selecting an antenna, we need to consider multiple parameters simultaneously to ensure it meets specific application requirements. These parameters include gain, radiation pattern, directivity, polarization, input impedance, VSWR (Voltage Standing Wave Ratio), return loss, size, weight, interface type, operating environment, etc. Among these, antenna gain, directivity, radiation pattern, and polarization are important indicators for measuring antenna performance, and they play a significant role in optimizing signal coverage areas and improving communication quality.

The following figure shows the most common sector antennas and omnidirectional antennas:

Based on Guoxin Longxin’s wireless project practices, this article focuses on introducing how to select antennas in different scenarios, helping users understand the principles and application key points of antenna gain, antenna directivity, radiation pattern, antenna polarization, etc.

I. Antenna Frequency and Antenna Selection

There is a close connection between antenna frequency and antenna selection. The operating frequency range of an antenna determines the range of electromagnetic wave frequencies it can effectively receive and transmit. Different application scenarios have different frequency requirements, so selecting the appropriate antenna frequency is crucial for antenna selection. Antennas with mismatched frequencies cannot be used; otherwise, they will not only fail to amplify signals and affect the normal operation of the wireless system but may even damage the equipment.

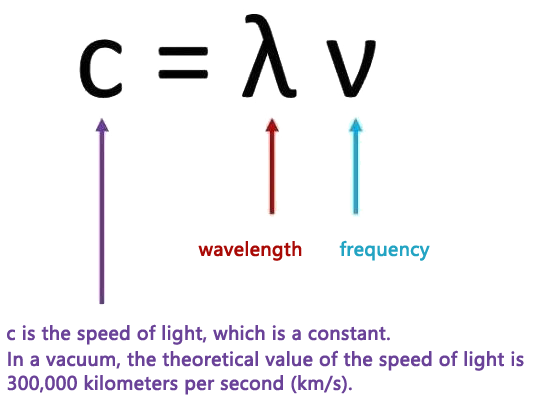

In principle, the frequency of an antenna is closely related to its physical size. According to the basic formula of electromagnetic waves, wavelength is inversely proportional to frequency, meaning the higher the frequency, the shorter the wavelength.

Therefore, the length of an antenna is usually related to the wavelength of its operating frequency. Common designs are 1/4-wavelength or 5/8-wavelength. For example, at a center frequency of 150 MHz, the wavelength is approximately 2 meters, while at 430 MHz, the wavelength is about 0.7 meters. This means that high-frequency antennas can typically be designed smaller, whereas low-frequency antennas require larger dimensions.

When selecting an antenna, the first step is to determine the frequency range required for the application. For instance, Wi-Fi communication typically uses the 2.4GHz or 5GHz frequency bands, while Bluetooth devices operate within the range of 2.4GHz to 2.485GHz. If the application needs to work within a specific frequency band, the antenna’s frequency range must match it.

In addition, the antenna’s frequency range affects its performance indicators, such as Voltage Standing Wave Ratio (VSWR) and gain. VSWR is a crucial parameter for measuring the matching degree between the antenna and the transmission line, and it is generally required to be less than 1.5. Near the antenna’s center frequency, the VSWR is usually minimized, and the efficiency is maximized. Therefore, when selecting an antenna, it is necessary to ensure that the VSWR within its operating frequency range meets the requirements.

In conclusion, the antenna’s frequency is one of the key parameters in antenna selection. It not only determines the antenna’s physical size and performance but also must align with the specific application’s needs. Only by choosing an antenna with the appropriate frequency can the efficient operation of the wireless communication system be ensured.

II. Antenna Gain and Antenna Selection

Antenna gain is the ratio of the power density of the signal produced by an actual antenna at a point in space to that produced by an ideal radiating element, under the condition of equal input power. It quantitatively describes the degree to which an antenna focuses the radiated input power. Simply put, the higher the antenna gain, the stronger the amplification of the wireless signal, and thus the farther the signal can travel and the wider the coverage area.

Antenna gain is a core concept in antenna design, primarily based on two aspects: directivity and efficiency. When we consider the directivity of an antenna, it refers to its ability to concentrate energy in a specific direction, thereby increasing the signal strength in that direction. An ideal antenna is like a spotlight, focusing all its energy within a small area to enhance the signal strength towards the target. The efficiency of an antenna refers to its ability to convert input power into radiated electromagnetic waves.

Typically, when designing an antenna, we aim to minimize energy loss as much as possible while converting input power into electromagnetic waves more efficiently, thereby increasing the antenna gain. Unless specifically stated otherwise, the antenna gain usually refers to the gain in the maximum radiation direction. Under the same conditions, the higher the gain, the better the directivity, and the farther the radio waves can propagate, i.e., the coverage distance increases. However, the higher the antenna gain, the more compressed the beamwidth becomes, resulting in a narrower lobe, which leads to poorer coverage uniformity. This is why high-power antennas have a narrow coverage range but a long communication distance.

The parameters representing antenna gain are dBd and dBi. dBi is the gain relative to an isotropic point source antenna, which radiates uniformly in all directions. dBd is the gain relative to a half-wave dipole antenna, where dBi = dBd + 2.15. Under the same conditions, the higher the gain, the farther the radio waves can travel.

The calculation formulas for the antenna gain (dBi) of commonly used different antennas are as follows:

(1) The narrower the antenna’s main lobe width, the higher the gain. For general directional antennas, the gain can be estimated using the following formula:

G (dBi) = 10Lg {32000 / (2θ3dB,E × 2θ3dB,H)}

In the formula, 32000 is a statistically derived empirical value. (2θ3dB,E) and (2θ3dB,H) are the half-power (3dB) beamwidths of the antenna in the two principal planes (E-plane and H-plane), respectively.

(2) For parabolic antennas, the gain can be approximately calculated using the following formula:

G (dBi) = 10Lg {4.5 × (D/λ0)²}

In the formula, 4.5 is a statistically derived empirical value. D is the diameter of the parabolic reflector, and λ0 is the center operating wavelength.

(3) For vertical omnidirectional antennas, there is the approximate calculation formula:

G (dBi) = 10Lg {2L/λ0}

In the formula, L is the length of the antenna, and λ0 is the center operating wavelength.

When considering the practical use of antenna gain, different calculation formulas need to be used according to the type of antenna to meet the gain requirements.

Because the vast majority of antennas are passive devices, their gain is generally an inherent attribute determined at the factory. As long as the frequency remains unchanged, their gain specification remains constant. Guoxin Longxin reminds users of several common misunderstandings regarding “gain” in antenna selection:

- Exaggerated Specifications: Obtaining the true gain value of an antenna is difficult without specialized laboratory environments (such as an anechoic chamber, or non-reflective chamber, lined with pyramidal absorbing material to absorb most electromagnetic energy incident on the six walls, effectively simulating free-space testing conditions independent of outdoor interference, making it an ideal facility for measuring antenna performance) and specialized equipment (such as a spectrum analyzer or other signal receiving equipment and an isotropic radiator). This inevitably leads to cases of “exaggerated” or falsified specifications in industry applications. Therefore, choosing a reputable supplier is crucial. Moreover, practice is the sole criterion for testing truth, meaning the antenna must meet on-site operational requirements, not just have high specifications on paper.

- Suitability is Key: Antenna gain is only one of the important indicators for antenna selection, not the sole criterion. Furthermore, as the saying goes, “too much of a good thing can be bad.” Excessively high gain, like excessively low gain, can exceed the communication strength threshold of wireless devices and adversely affect communication. Therefore, when selecting an antenna, users must do so under the guidance of experienced technical personnel from Guoxin Longxin and avoid blindly pursuing high-gain antennas.

- Systematic Thinking: In scenarios with different requirements, the demand for antenna gain varies. When building a complex system, it is essential to consider the overall situation and select an appropriate gain to prevent excessively strong signals in one part from interfering with other parts. In practical applications, using a high-gain antenna when the gain requirement is low not only yields poor results but the excessively high gain may also cause uneven wireless signal coverage, degraded wireless signal quality, impaired wireless system performance, and even signal leakage to other networks or devices, causing mutual interference. For example, there are usually many wireless devices on an operator’s communication tower. If the transmit power of one device is too high, it will cause mutual interference with other devices. Typically, the device’s transmit power is reduced to mitigate interference, which has a similar effect to selecting a low-gain antenna.

III. Antenna Directivity and Antenna Selection

Antenna directivity refers to the ability of an antenna to radiate electromagnetic waves in a specific direction or to receive electromagnetic waves from a specific direction. Different antennas have varying capabilities to radiate or receive in different directions, which reflects the directivity of the antenna. It is important to note that when an antenna transmits or receives electromagnetic waves, its radiation intensity or reception capability is not the same in all directions. This difference gives the antenna specific directivity, allowing it to radiate or receive electromagnetic waves more effectively in certain directions.

Antenna gain is clearly closely related to antenna directivity. In fact, antenna directivity describes the antenna’s radiation capability in a specific direction. We can graphically display the radiation intensity distribution of an antenna in various directions, which intuitively reflects the directivity characteristics of the antenna; this is the radiation pattern. The narrower the main lobe and the smaller the side lobes of the antenna pattern, the higher the gain.

Note: An antenna is a passive device and cannot generate energy. Antenna gain only represents the ability to effectively concentrate energy to radiate or receive electromagnetic waves in a specific direction.

The directivity characteristics of an antenna influence the shape and features of its radiation pattern. For example, an antenna with good directivity typically has a narrow main lobe and low side lobe levels, which is manifested in the pattern as a sharp main lobe and fewer side lobes, as shown in the vertical lobe pattern of an omnidirectional antenna. Conversely, we can also infer the directivity characteristics of an antenna by observing its radiation pattern. For instance, if a radiation pattern has a narrow main lobe and few side lobes, we can judge that the antenna has good directivity.

Therefore, this also means that antennas with different functions and gains, such as omnidirectional antennas and directional antennas, can be obtained by changing the antenna’s directivity. These are the two common types of antennas classified based on directivity used in wireless communication systems.

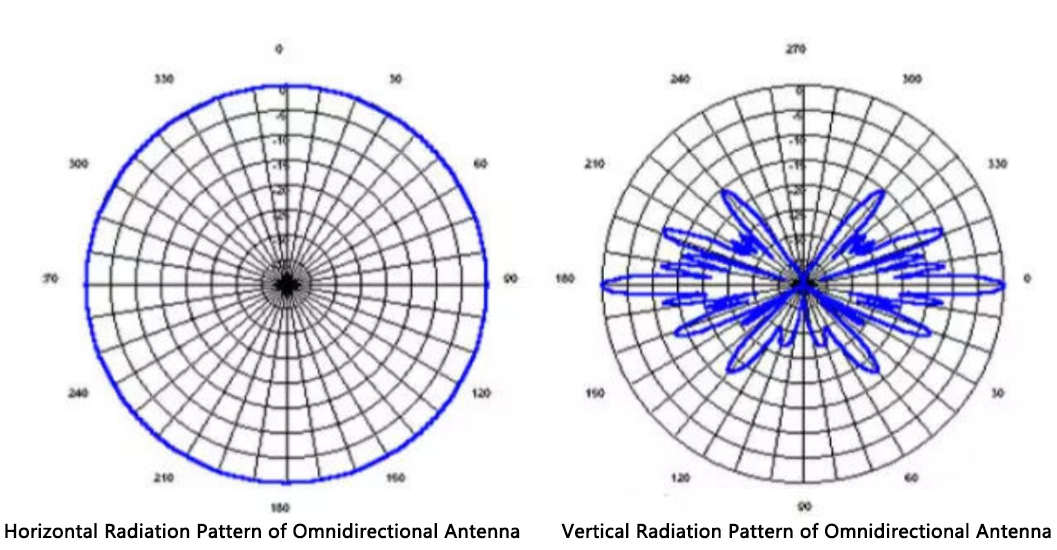

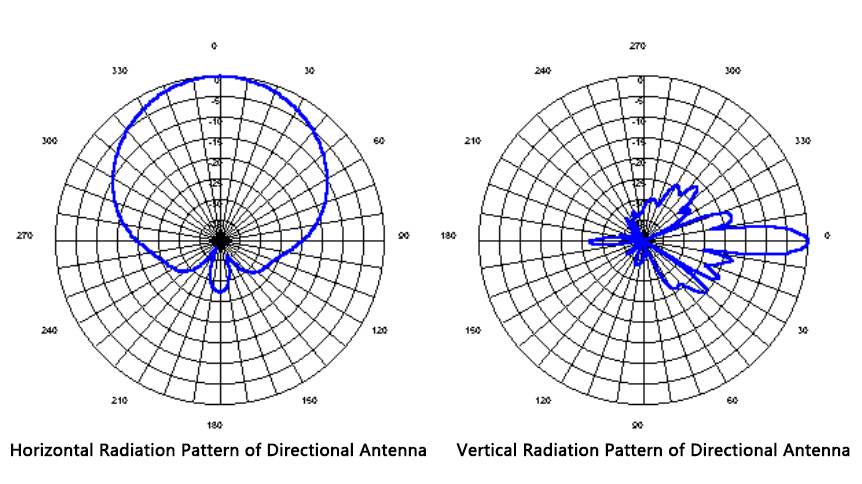

The following figures show the typical horizontal and vertical lobe patterns of an omnidirectional antenna and a directional antenna.

From the vertical lobe patterns of omnidirectional and directional antennas in the above figures, it can be seen that there is a largest petal in the radiation pattern, which is the main lobe mentioned earlier. This introduces another concept—the lobe angle. What is the lobe angle? The lobe angle generally refers to the lobe width of the antenna, i.e., the angular width formed at 3dB below the peak of the main lobe in the radiation pattern, also known as the beamwidth or half-power angle.

In general, for antennas of the same frequency and size, the larger the lobe angle, the lower the gain. For example, a 120-degree sector antenna (whose radiation direction presents a 120-degree fan-shaped area on the horizontal plane) has a lower gain than a 60-degree sector antenna. Of course, this is related to the R&D and technical capabilities of the antenna manufacturer and is not absolute.

Currently, for dual-polarized antennas commonly used in cellular mobile communication, WiFi, microwave, and private network communication, the lobe width is generally divided into horizontal lobe width and vertical lobe width, and the corresponding lobe angles are also divided into horizontal lobe angle and vertical lobe angle. Usually, the lobe angle determines the coverage range of the antenna. The horizontal lobe angle refers to the width of the main lobe in the horizontal plane in the radiation pattern, which determines the horizontal coverage range of the antenna; the vertical lobe angle refers to the width of the main lobe in the vertical plane in the radiation pattern, which determines the vertical coverage range of the antenna. The improvement of omnidirectional antenna gain mainly relies on reducing the vertical radiation lobe width while maintaining omnidirectional radiation performance on the horizontal plane.

The lobe angle is also related to the antenna’s sidelobe level. A well-designed antenna should have small sidelobes to reduce energy loss in non-main radiation directions.

In different practical applications, the requirements for the lobe angle vary, and it is necessary to select a suitable antenna according to the scenario:

- Fixed-Point Communication: Guoxin Longxin’s point-to-point fixed-point communication networking usually requires a narrow lobe angle to achieve long-distance directional transmission. For example, the lobe angle of the iMAX-6000 integrated antenna is only about 8 degrees. The base station unit (BS) of series products such as iMAX-8000H/S uses our customized high-gain 120-degree sector antenna, combined with client CPE devices integrated with small directional antennas (with a lobe angle of about 18 degrees), and its communication distance can reach 10 kilometers and above; when configured with a high-gain external directional antenna (with a smaller angle, for example, a dual-polarized 32dBi ultra-high-gain directional antenna has a lobe angle of only 3.5 degrees), the communication distance can reach 30 kilometers.

- Mobile Communication: In mobile communication applications such as vehicle-mounted and airborne, a wider lobe angle is required to cover a larger range. Commonly used antennas are omnidirectional antennas or sector antennas such as 60-degree, 90-degree, and 120-degree. There are also relatively special mobile scenarios, such as moving near and far along a vertical straight line, where directional antennas with a certain angle can also be used.

- Special Scenarios: For antennas used with special wireless communication systems such as waveguides and leaky wave cables, the lobe angle of the mobile terminal antenna is related to the actual situation such as the distance of the antenna arrangement. It needs to be calculated and designed according to the actual situation for further customization. Conventional antennas are not suitable.

IV. Antenna Polarization and Antenna Selection

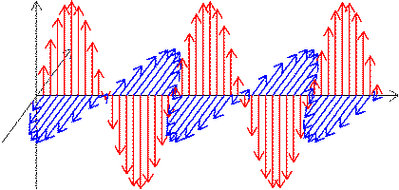

Antenna polarization refers to the polarization mode of electromagnetic waves radiated or received by an antenna in a specified radiation direction, specifically manifesting as the orientation and variation law of the electric field vector in space. Antenna polarization can be classified into several types:

- Linear Polarization — The electric field vector continuously varies along a line, which is usually parallel to the ground (horizontal polarization) or perpendicular to the ground (vertical polarization);

- Circular Polarization — The electric field vector rotates continuously around a circle in space. Depending on the direction of rotation, circular polarization can be further divided into left-hand circular polarization (LHCP) and right-hand circular polarization (RHCP);

- Elliptical Polarization — When the projection of the trajectory of the electric field vector’s endpoint onto the plane perpendicular to the propagation direction is an ellipse, it is called elliptical polarization. It can be regarded as a combination of linear polarization and circular polarization.

The polarization mode of an antenna affects its gain and beamwidth. In general, when designing an antenna with a specific polarization mode, the arrangement of oscillators is optimized according to that polarization direction to achieve higher gain and narrower beamwidth. For example, vertically or horizontally polarized antennas, through reasonable oscillator arrangement, concentrate more energy of electromagnetic waves in the specific polarization direction, thereby improving gain and reducing beamwidth. Under the same conditions, the gain of circularly polarized antennas is usually lower than that of linearly polarized antennas because circularly polarized antennas need to disperse energy into two rotation directions. However, in scenarios requiring overcoming interference such as multipath effects and polarization mismatch, the gain stability of circularly polarized antennas is better. Nevertheless, due to the more complex manufacturing process of circularly polarized antennas, their practical application is less common.

The polarization mode of an antenna also affects the shape and characteristics of the radiation pattern. For example, the radiation pattern of linearly polarized antennas usually has obvious directivity, while the pattern of circularly polarized antennas may be more uniform.

The polarization mode of an antenna may also affect its bandwidth. For example, certain types of circularly polarized antennas may need to maintain stable polarization characteristics within a narrow frequency range. Therefore, when designing broadband antennas, the impact of the antenna’s polarization mode on its bandwidth must be fully considered.

Currently, dual-polarized antennas (vertical + horizontal linear polarization) are commonly used in cellular mobile communication, WiFi, microwave, and private network communication. The so-called “polarized wave” refers to a radio wave where the direction of the electric field intensity is perpendicular to the ground, known as a vertically polarized wave; when the direction of the electric field intensity is parallel to the ground, it is called a horizontally polarized wave.

A key consideration in antenna selection regarding polarization is the need for mutual matching. Specifically, if the base station uses a dual-polarized antenna (combining vertical and horizontal polarization), the client device should ideally also employ a matching dual-polarized antenna. If the client uses two single-polarized antennas instead, transmission capability will inevitably be affected. However, in practical production, horizontally polarized antennas involve more complex manufacturing processes and have lower application volumes compared to vertically polarized ones. Thus, using vertically polarized antennas as a substitute for horizontally polarized ones is often a necessary compromise.

V. Usage Scenarios and Antenna Selection

There is a wide variety of antennas. In addition to omnidirectional and directional antennas, they can also be classified into helical antennas and microstrip antennas based on different application scenarios and performance requirements. In practical use:

- Omnidirectional antennas have a circular radiation range, making them suitable for scenarios requiring wide signal coverage and mobile devices;

- Directional antennas (note: original text mentions “全向天线” here, likely a typo; corrected to “定向天线”) have a fan-shaped radiation range, suitable for long-distance signal transmission;

- Helical antennas are typically used in satellite communication, radar, and other fields;

- Microstrip antennas, due to their small size, are commonly used in portable devices such as mobile phones and computers.

Many real-world factors constrain antenna selection:

- Antenna Size and Weight: If the communication pole has limited load-bearing capacity and the antenna exceeds size/weight limits, installation may be unstable. A falling antenna could cause personnel injury and property damage. For outdoor antennas, wind resistance is also a key consideration. To reduce wind resistance, one might choose a grid antenna with slightly lower gain or install a radome.

- Environmental Specifications: Generally, outdoor antennas must meet rigorous standards for temperature resistance (high/low), waterproofing, windproofing, dustproofing, rust prevention, and corrosion resistance. Indoor antennas should also be selected based on their operating environment.

- Special Scenarios: Many special scenarios demand unique communication solutions. For example:

- AGVs and robots often use omnidirectional antennas for mobility, but custom miniature directional antennas are preferred to avoid signal shielding by the vehicle body.

In conclusion, antenna selection involves multiple dimensions, including but not limited to size, weight, directionality, polarization, gain, and environmental specifications. The optimal solution is to comprehensively evaluate these factors and select an antenna that delivers appropriate signal gain for the actual use case.

Case Study: Guoxin Longxin Port Project

- Base Station (BS): Located at a fixed point in the command building, the wireless network only needs to cover the movement range of yard cranes. Sector antennas are typically used here.

- Yard Crane CPEs: Equipped with omnidirectional antennas because yard cranes move along fixed paths, and omnidirectional antennas facilitate easier signal reception from the BS.

- Quay Crane CPEs: Quay cranes are arranged in a straight line along the shoreline. Given their movement range and significant height differences, omnidirectional antennas are impractical. Instead, sector antennas are selected for better coverage alignment.

Overview

Antenna selection is crucial yet often overlooked in the field of wireless communication. Guoxin Longxin has compiled this article to provide users with guidance on antenna selection across different scenarios by delving into key antenna characteristics, indicators, and underlying principles. The core goal of antenna selection is to optimize the performance of wireless communication systems, enhance communication quality and efficiency, while comprehensively considering practical requirements and scenario-specific needs.

With the continuous evolution of wireless communication technologies, Guoxin Longxin’s research and application of antenna gain will become more extensive and in-depth, encompassing technologies such as Luneburg lens antennas and active phased array antennas. Furthermore, selecting or even customizing the most suitable antennas based on users’ scenario-specific technical requirements reflects Guoxin Longxin’s wireless technical capabilities and its ability to integrate industrial chain resources. For any questions or needs related to the wireless communication field, please feel free to consult Guoxin Longxin.

订阅评论

登录

0 Comments

最旧

最新

最多投票

内联反馈

查看所有评论